Is this the most spiritual destination in the Himalayas?

In the Himalayas of northern India, Ladakh is a land of jagged peaks and sprawling desert, where ancient monasteries are draped in prayer flags and Buddhist monks share words of wisdom with travellers passing through.

In the morning light the mountains glow brighter than gold, softer than silk. Row upon row, they weave through the region like gilded threads, embroidering the landscape as far as the eye can see.

I’m standing on a stupa (domed monument) at Ensa Monastery, hanging off its white-coned top and staring in stunned silence at my surroundings. Below, a herd of wild horses wanders the valley floor, two tiny foals frolicking carefree beside their mothers. In this stark moonscape of silver rock and dusty plains, with the Himalayas looming high above, life feels both precarious and immeasurably precious.

Precarious for me too, it seems, as I’m called down from my perch with a worried wave and beckoned inside. The ancient monastery was built almost a thousand years ago and, while many in the region have been modernised, almost nothing at Ensa has changed since. It clings to the edge of the mountainside, a haphazard clutch of buildings, home to only five monks and a scruffy mongrel with a flea-bitten tail.

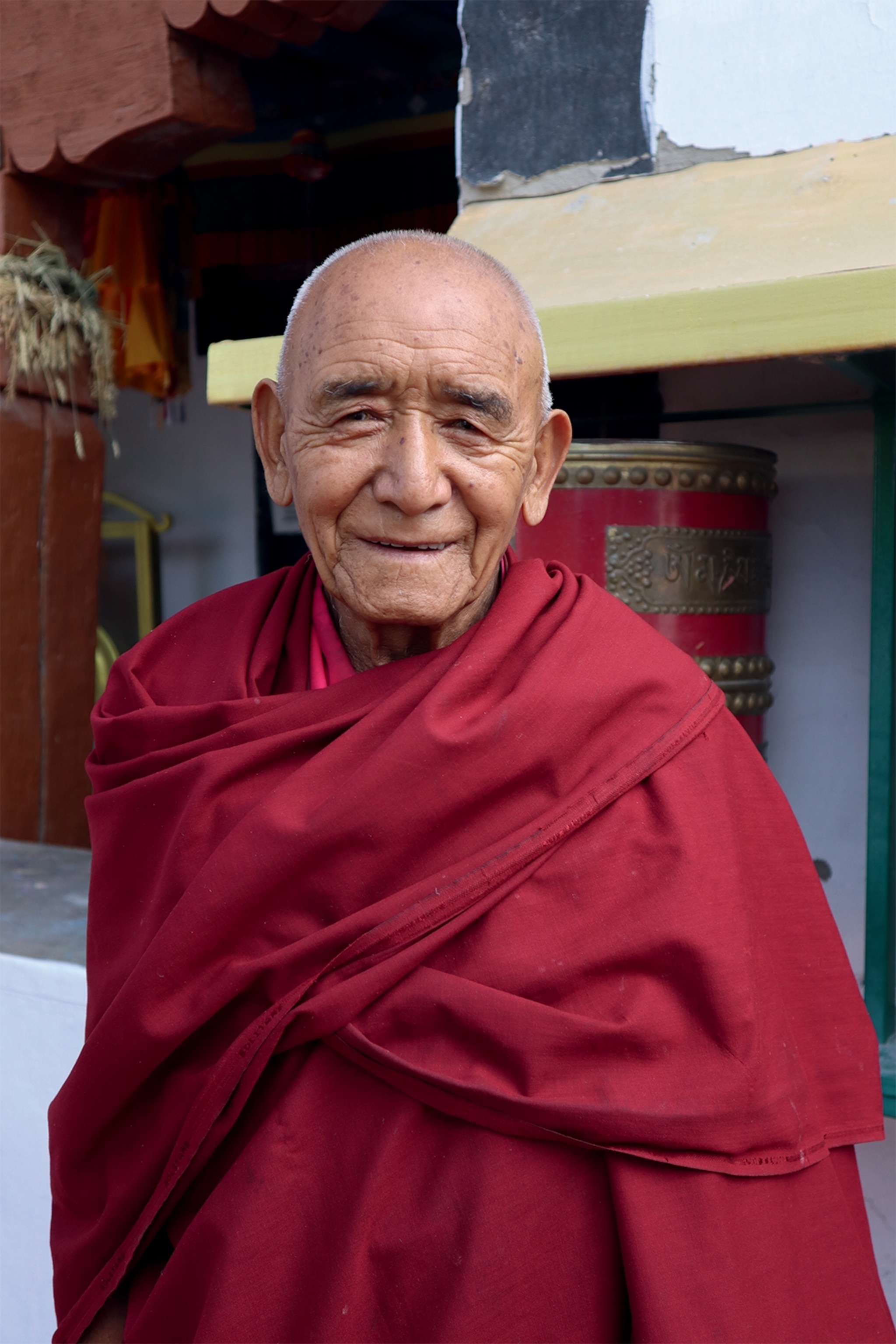

Tenzin, who had called me in moments before, now sits serenely in a corner, a scripture so ancient on his lap that as he turns the pages tiny fragments break off to join the dust dancing halo-like around his head. I kneel at his feet for a lesson in Buddhist philosophy, but he seems keener to learn what has brought me to this far-flung corner of Ladakh.

The Nubra Valley lies in the far north of the region and, using boutique Kyagar Hotel as a base, I’ve spent the last couple of days monastery-hopping. There are upwards of 100 in the region, from sprawling complexes like Diskit, which I’d visited the day before, sitting in a cloud of incense among 70 monks singing their daily sutras (scriptures), to tiny Ensa, where I’m kneeling now.

“Our postings may last anywhere between six months and a year,” Tenzin explains. “Do I get lonely here at the edge of the world? Perhaps, but it gives your soul room to grow, and just look at my surroundings. They’re a constant source of inspiration.”

His statement only becomes more profound the more I see of Ladakh, and I set off the following day to drive one of the world’s highest mountain roads: the Khardung La Pass. “Ladakh might be considered a desert,” my guide, Paldan, muses, “but just look at the colours. To me, these landscapes seem like something from another planet.”

He points out peaks streaked in shades of purple and blue, while the orange berries of stubby sea buckthorn bushes appear like tiny fires burning for the heavens. Fat-bottomed marmots scurry for their burrows as we pass, and a shepherd herding a flock of sheep 500-strong cuts a lonely figure on the mountainside.

“This peak is considered a source of good luck,” Paldan explains as we pause besides a boulder draped in thousands of prayer flags. “Monks make pilgrimages up here in May, the month the Buddha was born, often walking for weeks to reach its summit.”

We drive higher. The air feels thinner up here, the temperature has plummeted, and an icy wind buffets the car worryingly close to the cliff edge. But the scenery is nothing short of mesmerising: a sea of mountains stretching away into infinity beneath a sky of cerulean blue. “You really do feel closer to paradise up here,” Paldan says, almost to himself.

Time takes on a strange quality in the mountains, as though the laws that govern its passing have no power among the peaks, but all too soon, we’re up and over the highest point — 17,500ft, the same altitude as Everest base camp — and beginning our descent towards our next stop, not far from Ladakh’s capital.

Shel Cottage might just be the world’s most luxurious homestay. As I sit down on the rooftop terrace to a lunch of fresh salads and steaming chicken thukpa (Tibetan noodle soup), the views stretch out towards Matho Monastery, and my host Saumya explains that two Tibetan monks have been meditating in an isolated trance there for the past year. “Their bodies are said to be possessed by ancient spirits,” he says. “In February, a ceremony will see them emerge to predict the future of the village.”

But it’s not Matho Monastery I’m here to visit, and at 5am I’m roused in semi darkness for the short drive to Thiksey. Definition builds as we approach, like an artist is adding brush strokes to a canvas and I see why people have dubbed it ‘Mini Potala’. Cascading down a rocky outcrop, it really does resemble Tibet’s iconic Potala Palace, home to the Dalai Lama before he fled Chinese occupation in 1959.

We reach the rooftop as light starts to spill over the mountains and two monks begin blowing into Tibetan horns twice their height, heralding a new day. The first snow of the season has fallen and the world is dusted white, the horns’ low, melodic tones echoing mournfully through the valley.

I’m still lost in reverie when I sit among a sea of red-robed monks in the main prayer hall and am passed a cup of butter tea. “I can see you’ve been touched by this place,” an elderly monk beside me says with a knowing smile. “But nothing is permanent, and this moment will pass just as life does. What’s important is how you choose to live it.” His words resonate: ancient wisdom from a place frozen in time, to take back to a modern world.

How to do it

To subscribe to National Geographic Traveller (UK) magazine click here. (Available in select countries only).