Are we approaching the scientific limit to a hurricane's power?

Historically, it’s rare for a storm to exceed 200mph—but early research suggests it might not be so uncommon in the near future.

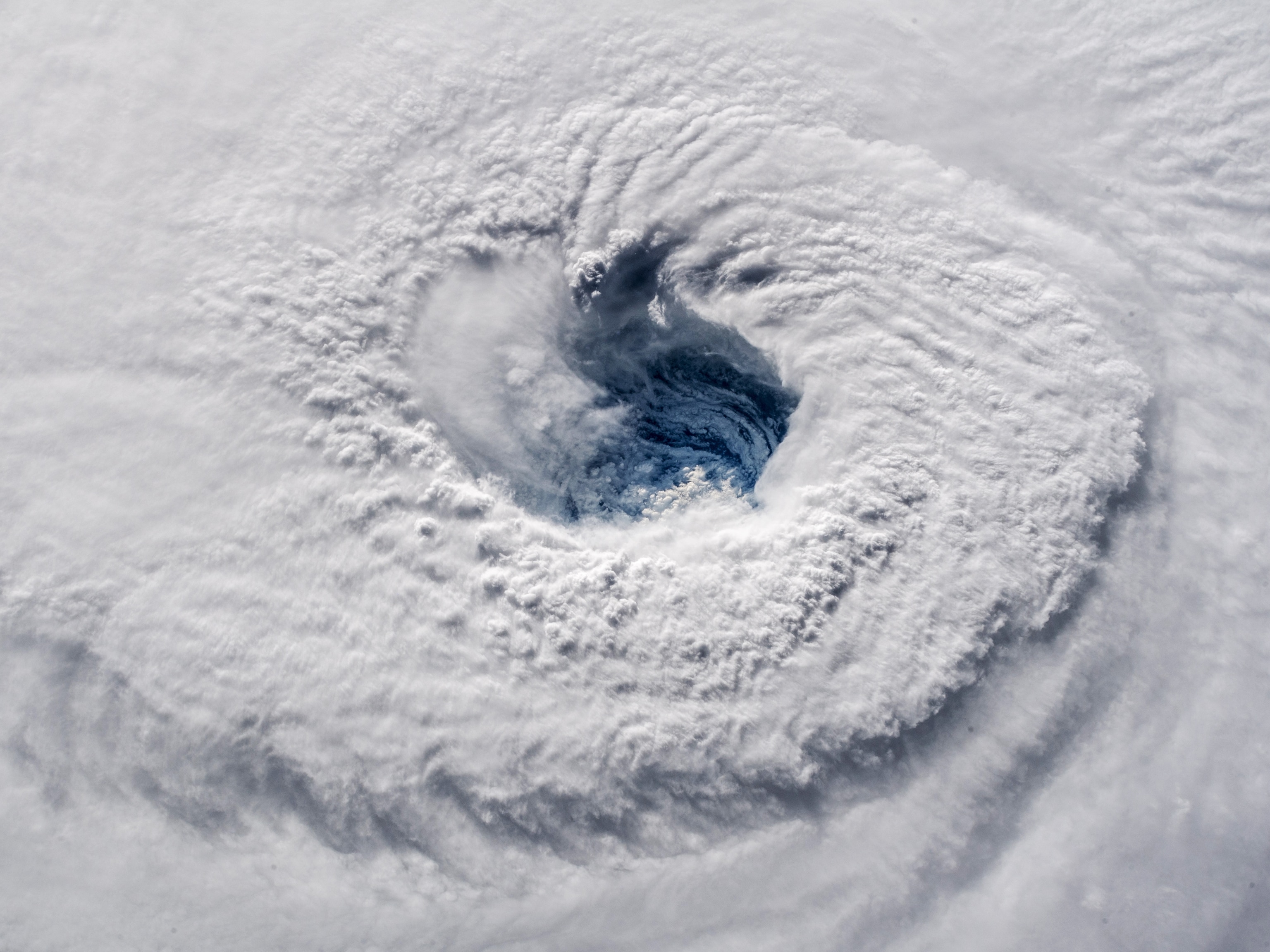

As Hurricane Milton bore down on Florida earlier this month, its strength and intensity magnified at a rapid pace as it became one of the most intense hurricanes on record in the Atlantic basin— and the strongest ever to hit the Gulf of Mexico late in hurricane season.

The storm formed as a tropical depression over the southwestern Gulf of Mexico on Saturday, October 5. By Monday, it was already a Category 5, with maximum sustained winds that peaked at 180 mph. Even though it had fallen back to a Category 3 storm as it came ashore on Florida’s central west coast, its speeds of up to 120 mph were still enough to destroy more than 120 homes and rip the roof off Tropicana Field.

Milton was the second Category 5 storm of the season after Beryl in July— making 2024 just the sixth year since 1950 (following 1961, 2005, 2007, 2017, and 2019) to experience two or more Category 5 hurricanes. The science connecting climate change to worsening hurricanes is increasingly clear; two recent analyses show that warming helped boost Hurricanes Helene and Milton. With warming temperatures on track to continue, how strong might the storms of the future be?

How warming temperatures supercharge storms

A number of factors help form a hurricane. According to Kerry Emanuel of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the two most important are the temperature of the ocean and the temperature of the air column up to about twelve miles.

In general, he says, the warmer those two elements are, the more energy a storm has available to develop into a tropical cyclone (known as hurricanes in the Atlantic and typhoons in the Pacific). Historically, he adds, nowhere on the globe has water been warm enough for tropical cyclone wind speeds to exceed approximately 200 miles per hour, and rare is the storm that comes close to that.

In fact, he says, “maybe one or two percent of all storms get close to this boundary.”

However, “as you raise the greenhouse gas content of the atmosphere, causing warming to increase, that limit does go up. So it may be that at the end of the century, if we are not successful at curbing greenhouse gases, the maximum value might be closer to 220 miles per hour.”

In a recent study, climate scientists Michael Wehner of Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and James Kossin of the First Street Foundation calculated that, with two degrees Celsius of global warming above pre-industrial levels, the risk of storms that approach the present theoretical speed limit increases by up to 50 percent near the Philippines and doubles in the Gulf of Mexico.

As a result, they suggested the idea of a Category 6, for storms with maximum sustained winds of 192 mph or greater, and found that, between 1980 and 2021, five storms would have achieved that classification, all of them in the final nine years of the record.

Communicating more dire warnings

At present, hurricanes are rated from Category 1 to 5, based on maximum sustained wind speeds, on what is known as the Saffir-Simpson scale. (Typhoons and Indian Ocean cyclones use different scales.) Category 1 hurricanes have wind speeds from 74 to 95 mph; wind speeds in Category 5 storms are upward of 157 mph.

In their study, Wehner and Kossin suggested that, in a warming world in which intense storms become more frequent, the open-ended nature of Category 5 may be insufficient to convey the risks associated with the most powerful hurricanes.

“The scale is kind of useful for conveying the increased risk from climate change, because it reflects that the windiest storms are windier,” Wehner says. “But along with that comes the other hazards that are more dangerous as well: coastal storm surge, saltwater flooding, and inland freshwater flooding from rainfall are also exacerbated because of climate change.”

Indeed, he notes, a large, slowly churning storm that stays just offshore and drives large amounts of water onto land can be at least as devastating as a more compact storm with higher wind speeds.

“Superstorm Sandy wasn’t even a category 1 when it came ashore in New York and New Jersey [in 2012],” he notes. “But it was so spatially big that it was devastating.”

Another problem with the scale, he adds, is that it encourages people at risk to focus on the wind speed to the exclusion of other risk factors, and to sometimes drop their guard when that speed diminishes.

The biggest problem with more dangerous hurricanes isn’t necessarily wind, Emmanuel says. It’s water.

“There's 100 percent consensus among climate scientists that raising the temperature will increase the rainfall in hurricanes,” he says. “It's just very straightforward physics. So, the real increase in hazard from climate change isn't so much about the intensity increasing, although that's important. It's about the rain increasing.”