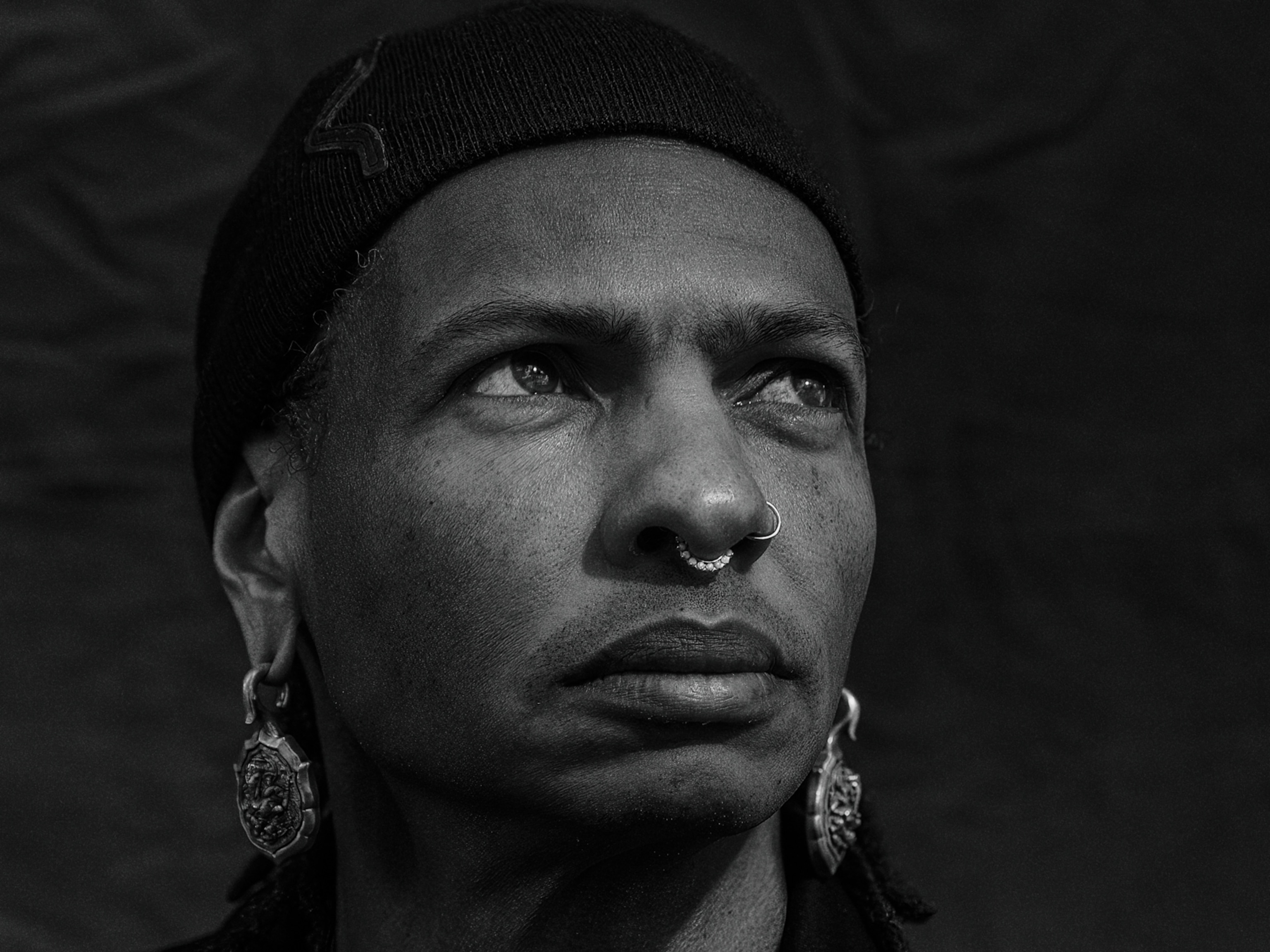

Kerllen Costa amplifies community-led conservation across Africa

For the ethnobiologist and environmental anthropologist, nurturing relationships is step one in protecting a landscape.

Deep in the remote floodplain of Angola’s Kwando River, National Geographic Explorer Kerllen Costa and his team were desperately searching for a campsite when they spotted an elder alone on a small island.

As their canoe approached the island the elder questioned him: “Why were the people with you watching river birds with their binoculars?”

When he explained they were a team of scientists on an expedition, the elder told him, “If he only looks at the bird, he won’t be able to understand how the bird communicates with the tree, how the bird interacts with the water.”

Costa asked him how he knew this and the elder replied:

“Well, because how would you know what’s in a landscape — what’s its story if there’s no people in it? It’s only the people that bring history to it.”

This is the origin of a quote that has guided Costa’s work as an ethnobiologist and environmental anthropologist through the rivers of the Angolan Highlands Water Tower: A landscape without people, is just a landscape. A landscape with people, has history and soul.”

Trekking through the Okavango River Basin

Sourced from the lakes and groundwater of the Angolan Highlands, the drinking water for millions of people flows through a river system into one of the world’s largest freshwater wetlands: the Okavango Delta.

Spanning across northwestern Botswana, the Okavango Delta is a unique biodiversity hotspot and is home to the world’s largest remaining population of elephants and other endangered species, such as the African wild dog and cheetah.

Since 2015, the National Geographic Okavango Wilderness Project (NGOWP) has worked to secure long-lasting protection for the Okavango Basin, from its source in Angola, to the Okavango Delta in Botswana. For decades, many of these source lakes and rivers have remained “undisturbed,” as Costa says, because they reside in a historical stronghold for the rebel forces of the forty-year-long Angolan Civil War.

Researching these source lakes and rivers strengthens the world’s academic knowledge base of this region. With more data, NGOWP can build a stronger case for the governments of Angola and Botswana to secure long-lasting protections for the Okavango Basin and Angolan Water Tower. As NGOWP’s Angola country director, Costa leads major river expeditions to gather this data, often going down rivers in dug-out watos (traditional canoes) and taking days to traverse dense forests in “the most remote parts of the landscapes of Southeastern Angola,” says Costa, by motorbike or foot.

But while these landscapes are remote, they are not unprotected.

As an African oral tradition, you don’t just listen. You then tell the story to somebody else for the story to live on.

Local communities have developed lifeways over generations that protect and respect their homeland. Understanding what it means to protect these environments, means meeting, listening, and knowing the people who live there.

“You sit, you stay, you observe, you absorb,” says Costa, “that's when the other people around you will then come to you to speak, after they feel comfortable.”

Costa’s work as a biologist and environmental anthropologist hinges on building relationships of trust with local communities. He often spends nights in villages listening to local elders share their beliefs on existence and has spent weeks trekking through remote parts of the forest with local hunters. For his work with local communities, he was awarded a 2024 Wayfinder Award by the National Geographic Society.

He says the circumstances of the Angolan Civil War made him feel more connected to people and the environment. Costa feels this experience has allowed him to “bond differently with people” in his work with NGOWP, to better understand their different realities.

“And it takes a while for you to understand, but intrinsically, I know that a person can’t be poor if they have never starved, if they always have food,” says Costa.

“A person can’t be poor if they have their own system of traditional healing. A person can’t be poor just because they don’t have a school, because they have their own traditional ways of transmitting knowledge. And it’s been functioning for millennia. That’s why they’re there and their environment is preserved.”

Starting at the source

Costa says his younger self wouldn’t have imagined he would be working in conservation, but he is where he should be. He feels life has stepped in several times to show him his path, and he’s chosen to follow it, not knowing what could come next.

“And it has happened that it’s taken me to some very interesting places.”

Growing up in Luanda, Angola’s capital city, Costa and his family traveled throughout the country due to his father’s job as a helicopter pilot in the Angolan Air Force during and after the civil war. Costa studied to become a pilot like his father, while simultaneously pursuing a career as a professional soccer player.

With savings and the support of his family, he was able to travel to England after invitations for trials at professional soccer clubs, with a backup plan to start university, but a call from his younger sister brought him back to Angola to support his family. Back home, he played for local clubs and the under-20 national team.

Costa later worked at a customs broker for about eight years, before a trip to Cape Town convinced him to attend university in South Africa. When he graduated, his sister told him of a job opening.

“When I was finishing the degree my sister said, ‘Listen, there’s this advertisement at Nat Geo. They’re needing someone to upload and download data from the watches of the scientists.’”

Costa applied but didn’t get the job because the position had already been filled, but the team liked his Curriculum Vitae and asked him to be a volunteer on the then-nascent, year-old National Geographic Okavango Wilderness Project. He began in 2016 as a community liaison, setting up camera traps and logging data for the project.

It was a series of moments during his start with NGOWP — following hunters through the bush to find a source lake, listening to village elders speak about the formation of the stars — that challenged what Costa said was his initially “romanticized idea” of conservation.

“I very quickly realized that there’s a lot more than just the landscape. There’s a lot more than just the natural heritage. There are people, there’s history, there’s traditions, there’s beliefs,” and he says this realization placed him in a sort of limbo.

He understood that the people living where NGOWP sought to study had protected their environment through knowledge and practices accrued over generations. “But the conservation industry is looking at it in a completely different way.”

“There were several different moments where the local people were saying, ‘Listen, you and your scientists, you might say this, but we know for sure it’s this for a reason,’” says Costa.

He reflects on an expedition where the team looked to traverse a river but first needed to locate its source.

The team sent Costa as a community liaison to work with local hunters to spot possible obstacles and locate the river’s source.

“I’ve always been very attentive to what the local people say,” Costa says, and after asking village elders about the source’s location, he trekked three days to the source, marked its location and returned to the team’s camp with the coordinates.

The project’s team of 20 people moved out, taking 10 canoes until the terrain forced them on an overland route towards the source. When Costa gave the source’s coordinates, it was a different direction than what the scientists predicted.

One of the scientists told Costa, ‘‘No, according to what I saw on the map, the source should be this one here because it’s the longest, the furthest away point from where the river ends.” Costa went out and asked the elder again, who immediately replied:

“Tell him that the river was named this because one of my ancestors was here, and he identified this to be the source of this river with this name. So, whatever scientific parameters you’re using to now identify the source, those are not real.”

This was one of many moments throughout Costa’s expeditions when Indigenous knowledge and methods showed the critical importance of practicing community-focused conservation. After speaking with elders and local groups, he realized they were sharing all this information, reflections and thoughts “not just for me to listen.”

“As in African oral tradition, you don’t just listen. You then tell the story to somebody else for the story to live on.” The quote is adapted from a traditional leader's, named Satchindamba, Costa notes.

This tradition lives on in Costa’s fieldwork and the Tribeca award-winning “Guardians of the River'' podcast. He hosts the eight-part series, which details the stories of the people and communities who have been protecting the Okavango River Basin. The podcast, in a way, is “internalizing this oral tradition, making something result out of it and not just disappear.”

The conversation surrounding conservation

The human approach Costa puts at the helm of his team’s efforts is part of a paradigm shift in the world of conservation.

“That can shock some of the more conservative ways of thinking in terms of conservation. And there still is that difficulty to try and understand we shouldn’t create a national park. No, because it’s blocking access to people who have been going to those areas for millennia,” Costa stresses.

“Why not allow people to still roam and use the systems that they already used for the last five generations? Where they only use resources according to daily needs and where they respect certain concepts?”

Costa is also building on his experience and knowledge from traversing the Okavango Basin, to understand other African river systems, and their implications for the continent’s future food and water security.

Costa's next expedition will take him to the largest river in Angola: the Kwanza, which feeds some of Africa’s most crucial river systems. The river is different from the crystal clear and sandy-bottomed rivers his team previously traversed in the Okavango Basin. The Kwanza’s riverbed is rocky and cloudy, its waters cut west through the Angolan Escarpment and empty into the Atlantic Ocean. Also, the Kwanza's rapids and large population of hippos pose a big risk to Costa and his team, but these new challenges have not changed what he defines as success.

“I really feel success should be people being able to still manage their own natural heritage and still living according to their traditions,” Costa says.

“If you go to rural Africa, it’s probably the most preserved place in the world because of how they live. And it’s only when we internally value that and elevate that, that it’ll be implemented at the core.”

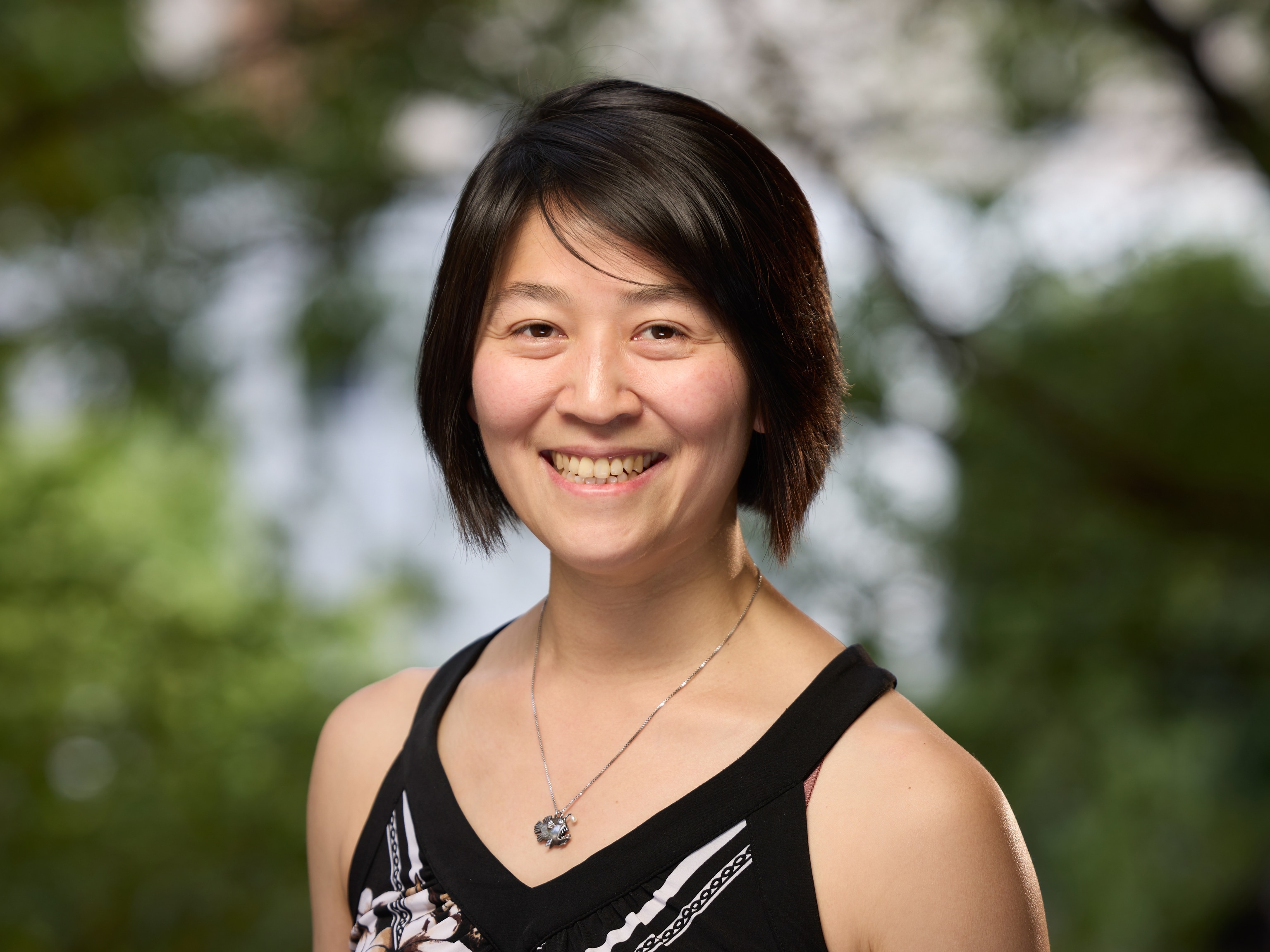

ABOUT THE WRITER

Olatunji Osho-Williams is the 2024 Content and Editorial Strategy Intern for the Society. He looks to capture stories of human connection and history in his writing. In his free time he enjoys video essays and creative writing.