Scientists found life in a volcano’s ‘lava tubes’—life on other planets could be next

A Canary Islands volcano pushed rivers of molten lava through the earth. Now scientists and explorers trek through the cooling underground, looking for insights into life on this planet—and perhaps on others.

We could be on another planet.

A craggy, hostile surface stretches as far as the eye can see, framed by slopes of black ash. These are the new lava flows on La Palma, in the volcanic Canarian archipelago, off the coast of Morocco. They appeared in the fall of 2021, when, for three months, more than 50 billion gallons of molten rock erupted from the island’s Tajogaite volcano.

Transit through most of the lava field is still reserved for scientists and environmental officials. I’m accompanying Octavio Fernández Lorenzo, vice president of the Canary Islands Speleology Federation. Alongside researchers from the Geological and Mining Institute of Spain (IGME), Fernández is responsible for exploring and surveying the tunnels that lava left in its wake. Known in most scientific literature as pyroducts or lava tubes, they have a more poetic name here on La Palma: caños de fuego, fire pipes.

Fernández hands me a helmet, checks our water supply, and heads toward a white fence where a sign warns us not to cross. The road that brought us to this place cuts off abruptly and disappears under the blanket of lava. It feels as if we’re abandoning civilization.

(Lava built this island—then entombed towns in stone.)

Fire pipes can be found almost anywhere on the planet where there is, or has been, volcanic activity. In contrast to typical caves, formed over millions of years, these cavities are made in a geological instant. But not all volcanoes create lava tubes. The eruption must be long enough to expel adequate lava. That lava must be hot enough and composed of the right materials to remain fluid. And it has to descend a slope, at the right speed.

At around 1800 degrees Fahrenheit, pahoehoe—“smooth” in Hawaiian—lava can flow. “It’s the same word used to define a calm sea,” says Fernández. I can picture it quite vividly. A sea of incandescent, syrupy lava advances, spilling downhill. The outer layer cools on contact with the air and begins to solidify, forming a crust that will become the roof of the tube. The lava continues to stream, unimpeded for miles, under that thermally insulated cover. When the eruption dies down and the channels drain, the result is a subterranean labyrinth of hollow tunnels separated from the surface only by the volcano’s skin.

Leaning on a long white stick, which helps him move nimbly over hardened lava, Fernández looks a bit like a wizard from The Lord of the Rings. He studies our strides, as if he were the guardian of this newborn space. “Step where I step,” he warns. “This whole environment is extremely fragile.” It seems paradoxical that this imposing landscape, once capable of swallowing houses and banana plantations, could now be vulnerable.

Our hike to the tube takes an hour along a slope of sharp, living rock. This is aa lava, a Hawaiian term for “rough and stony” that many believe sounds like what someone walking barefoot on this jagged surface might say. Phrases from Hawaii’s active and intensely studied hot spots have been adopted by volcanology. Other languages have their own words that evoke images. For example, in Spanish this barren terrain is called malpaís, or bad land.

We walk slowly. Fernández picks up a tiny, immaculately white pyroclastic rock and hands it to me. It’s what researchers call restingolite, after the eruption in the La Restinga region of the neighboring island of El Hierro in 2011, when hundreds of pieces of whitish rock were found floating on the ocean, giving rise to a scientific debate that, unlike the eruption, has yet to die down. One hypothesis for their origin: They’re bits of the foundation on which La Palma grew, ancient ocean sediments from that two million-year-old seabed. Looking at the small fragment brings about an inexplicable feeling of vertigo. David Sanz Mangas, a geological engineer specializing in the study of extreme events and heritage at IGME, puts it this way: “It’s like looking out a window into our past.”

(Rediscover our coverage of the Canary Islands volcanic eruption.)

Barely a month into the eruption on La Palma, scientists detected lava tubes. They’re not obvious to the naked eye; drone imagery captured during the eruption helped predict their possible routes. One tube was discovered in June 2022, six months after the eruption ceased, as workers were starting to build a new road over the hardened flow. When they came across a cavelike space, they had to pause. And that was when Sanz, who had relocated from Madrid to the Canary Islands to study the eruption’s aftermath, joined the team and began exploring the newborn fire pipes of La Palma.

“Based on field data obtained in the Hawaiian archipelago, the place with the largest volcanic cavities in the world, we assumed exploration of the tubes could begin about two years after the eruption,” he says. But here “we saw that, with difficulty, it was accessible.”

Drones are crucial to fieldwork. “The first step was to begin a series of thermal flights that would monitor the open holes in the lava field,” he says. “And to start exploring them little by little.”

The so-called red tube is a product of the lava rivers that, three years ago, flowed down into the small town of Todoque. Today a pair of entrances about 200 feet apart allow air to circulate. “Instead of hot air coming out, the mouth sucks in fresh air from outside,” Fernández says. “This is the best laboratory we have right now to learn how the lava flows cool.” We turn our headlamps on, crawl in, and confront the surprising reddish color of the walls. On the ceiling we see dark brown lava stalactites hanging like droplets that solidified before they could fall and are now suspended forever. They look like melted chocolate.

Inside the tube, the air is cooler than the walls—anywhere from 120 to 210 degrees, according to a probe. We balance against these walls with our gloved hands as we move forward, step by step. The humidity and the mix of temperatures give the cave the pleasant sensation of a Turkish bath.

With a thermal drone, Fernández takes temperature readings. About a hundred yards in from the mouth, he tells us to stop: The heat is increasing significantly. Not far ahead, the tube narrows and exhales a temperature of more than 480 degrees. In the video feed, the air shudders like a mirage.

This mouth is just one of more than a hundred identified so far, mostly by drone flights overhead—though some remain too camouflaged to spot from the air. Just a tiny number have been explored. Openings are viable only if the temperature allows. In lava flows up to 65 feet thick, cooling can go on for two and a half years; at 150 or 200 feet thick, it might be 20 years.

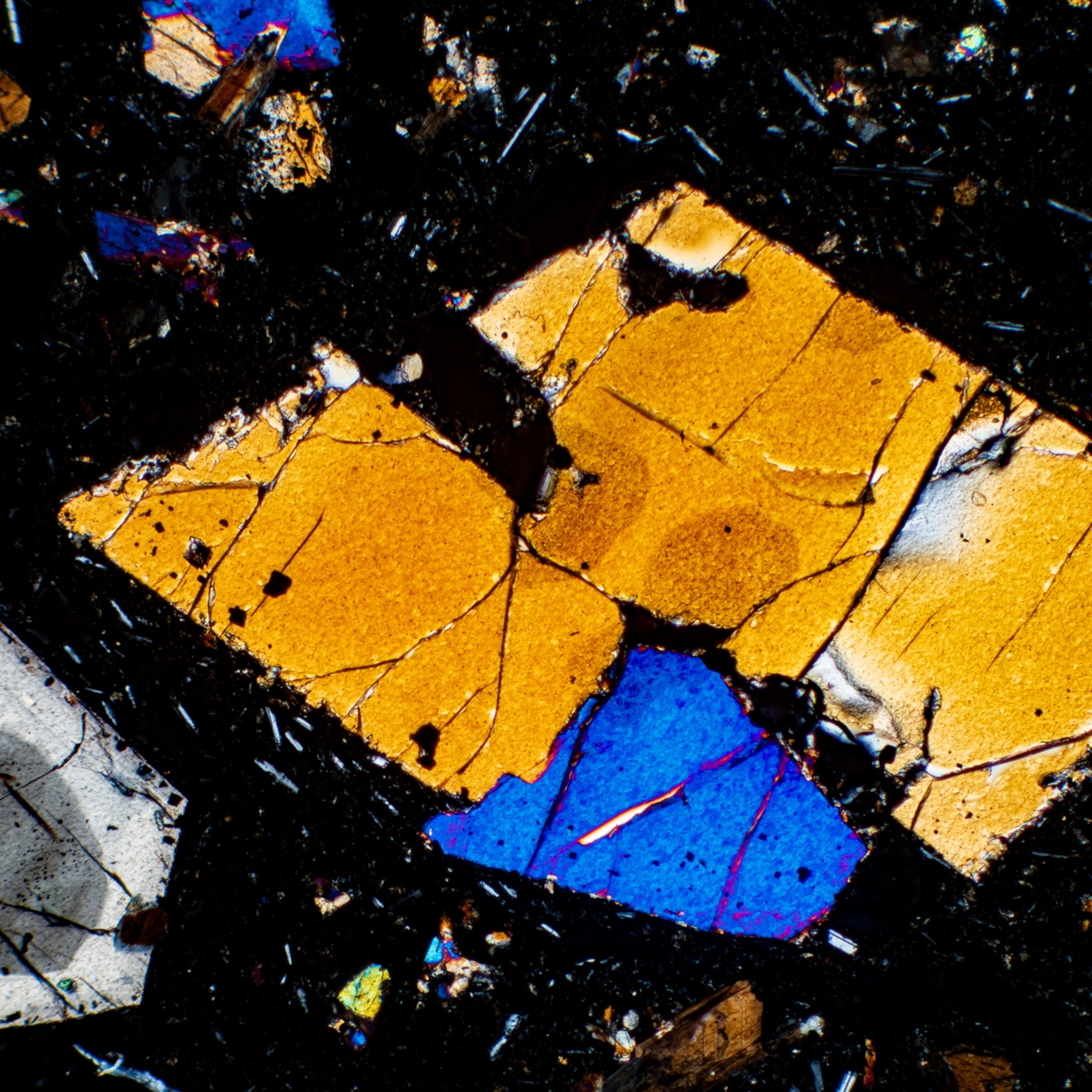

(These crystal lava shards are ‘four-dimensional videos’ of a volcano’s underworld.)

It’s too soon to predict how far these tunnels reach. Scientists believe that this network may be composed of up to three overlapping levels. Sanz thinks it could be the most extensive tube system in Europe. That title is currently held by the Viento-Sobrado cave system beneath Mount Teide on the neighboring island of Tenerife. With more than 11 miles of tunnels, it was considered the largest volcanic tube in the world for a brief moment until, in 1995, a man named Harry Shick found a cave entrance in his yard on the island of Hawaii. It would turn out to be the access point to more than 40 miles of tubes, branching out from the Kilauea volcano.

There is much to learn from these tunnels, and perhaps not just about our world. Ana Zélia Miller, a geomicrobiologist from Seville’s Institute of Natural Resources and Agrobiology, is the daughter of artists. The course of her life changed when her parents gave her a microscope at the age of nine. Since then, she has focused her lens on those small life-forms that go unnoticed by the human eye. Her first discoveries were made in La Palma’s fire pipes, studying their peculiarly gelatinous speleothems, or mineral deposit formations.

Miller’s research on extremophile species, especially bacteria capable of obtaining the energy to develop from inorganic matter, led the European Space Agency to recruit her for its Pangaea-X project. The mission was to train astronauts in the collection and analysis of microbial samples on the nearby island of Lanzarote inside a lava tube whose conditions appear comparable to lava tubes on the moon and Mars.

Since 2009, when a Japanese space probe discovered the Marius Hills Skylight—a possible entrance to one of the moon’s volcanic tubes—the scientific community has been studying the similarities between terrestrial volcanic tubes and their planetary counterparts. For Miller, the question is no longer if we will find life on other planets, but when.

“Martian and lunar caves differ greatly from ours in terms of environmental conditions and gravity, which affect their size and stability. However, their formation and surroundings have more in common with terrestrial ones than one might think,” says Francesco Sauro, a European Space Agency scientist and National Geographic Explorer. If there is, or has been, life in these otherworldly lava tubes, it could be microbial, as it is in the fire pipes of La Palma.

“The recent eruption on La Palma gives us a unique opportunity to learn about the pioneering microbiota in these newly formed lava tubes,” says Miller. The island’s volcanic tubes are already inhabited. Miller’s team has identified known bacteria as well as other life—belonging to the phyla Pseudomonadota and Bacteroidota—which could ultimately be identified as new species.

(Dramatic photos show the 2021 La Palma volcanic eruption.)

La Palma’s Volcano Route, an old hiking trail that reveals the island’s distinctive landscape, is open again. From there, a path, still carpeted with ashes, leads to another partially explored tube, known by scientists as hornito bonito—pretty little oven. We come across a group of tourists who have hiked to see the main cone of the volcano, recently named Tajogaite, “cracked mountain” in the island’s native language. The rest of the area requires accreditation, and even a gas meter and masks, because conditions can vary from one moment to the next.

The ash field is deserted, as unspoiled as the eruption left it, and covered with small craters. Each one houses a rounded stone, like an oyster with a pearl. The stones are viscous fragments spat out by the volcano, smoothed by friction with the air. Volcanic bombs, says Fernández. He takes one in his hands to show me and then puts it back in its place. They are part of this virgin landscape, at least until someone decides to start taking them as souvenirs.

“The ideal would be to create a network of marked and monitored trails so that everyone could enjoy this new geological richness, without damaging it and without encountering any risk,” Fernández says. He pays close attention to our steps and turns at any suspicious creak. The layer of hardened lava is a thin biscuit, not even two inches thick. Underneath there may be a bubble, a crack where the temperature can exceed 900 degrees.

The hornito bonito rises up like an artisanal oven or a sandcastle. “The hornitos are like mini-volcanoes,” explains Fernández. “This one was formed in just three days.” It appeared right above the north face of the volcano’s main cone, when a jet of lava shot a hundred feet into the air. As it lost strength, gases began to bubble up, expelling spatters that piled up until they formed a truncated, conical tower.

A nearby entrance is a huge hole that descends into the tube, giving an idea of the lava waterfall that must have circulated, the edges solidifying around it. A light white powder seems to settle on everything, condensing into tiny white stalactites, as thin as needles—researchers are still studying their composition. They are ephemeral minerals, doomed to transform and disappear with every drop of water. Maybe by the time we know what they are, they won’t exist anymore.

The earth here gives you a sense of reverence toward places touched by disasters. I turn my headlamp off to feel the darkness. The silence and the solitude are breathtaking. Eventually, we cross the lava field back to our cars. It’s raining, and the puddling water kicks up clouds of steam. Our clothes are soaked, but I don’t feel cold. Heat is still emanating from the living rock.

“My hometown is nestled within a volcanic crater,” says Arturo Rodríguez, a La Palma native. He has spent his career abroad, documenting elections in Haiti, refugees in Africa, and war in Myanmar, but returned to capture the recent eruption.

This story appears in the June 2024 issue of National Geographic magazine.