How Ouija went from quirky parlor game to the most feared spirit board in history

Once a beloved game that bridged the living and the dead, the Ouija board’s reputation has changed dramatically, from Victorian entertainment to a symbol of supernatural mystery.

To many, the Ouija board conjures stories of ghostly encounters and eerie warnings. Yet over a century ago, it was just a parlor game, offering lighthearted entertainment in Victorian homes.

First introduced in 1890 by the Kennard Novelty Company as a “wonderful talking board,” the simple piece of cardboard is marked with letters, numbers, and the words “yes,” “no,” and “goodbye.” Players place their fingers on a triangular pointer, which appears to move on its own to spell out messages in response to their questions.

As innocent as its design may seem, the Ouija board’s role in society has taken a darker turn. Over the past 130 years, it has transformed from a quirky pastime into a symbol of supernatural mystery, evolving into both a cultural icon and a source of fascination.

The birth of the Ouija board

The roots of the spirit board can be traced back to the 1840s when the Modern Spiritualist movement took hold and became a cultural craze. During this time, it became fashionable to host spiritual gatherings that featured psychic mediums, séances, tarot card readings, and, of course, talking boards, says Stephanie McGuire, curator of the Molly Brown House Museum, a Victorian-era museum in Denver, Colorado and the former home of Titanic survivor Margaret “Molly” Brown.

“They have a connotation now that is 180 [degrees] different from the way Margaret viewed Ouija boards in her day,” McGuire says. “Even more so than connecting with dead loved ones, it was also this wonderment—can I connect with something unknown, and can I know what my future holds?”

(Discover how the world went wild for talking to spirits 100 years ago.)

Beyond entertainment, talking boards offered solace in a time of loss and uncertainty. In post-Civil War America, when most families frequently experienced the sudden loss of loved ones, communicating with the dead was a normal, even necessary, way of coping with grief.

“Today, we are very removed from death,” says Robert Murch, an Ouija historian and chairman of the board at the Talking Board Historical Society. “We live way longer, we are way healthier, we don’t even want to look old. We do anything we can to push death away. And when you do that, you start to be [un]comfortable with it.”

Spirit boards provided emotional refuge for people in the 1890s, says Murch. “They became answers for things that didn’t have answers…allow[ing] you to talk about something and experience something that’s inexperience-able.”

(Séances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occult.)

However, this historical context can be challenging to appreciate from a modern perspective, says John Kozik, owner of the Salem Witch Board Museum in Salem, Massachusetts. “People today try to view the history with today’s eyes,” he says. “Because people are viewing death differently, they view Ouija differently.”

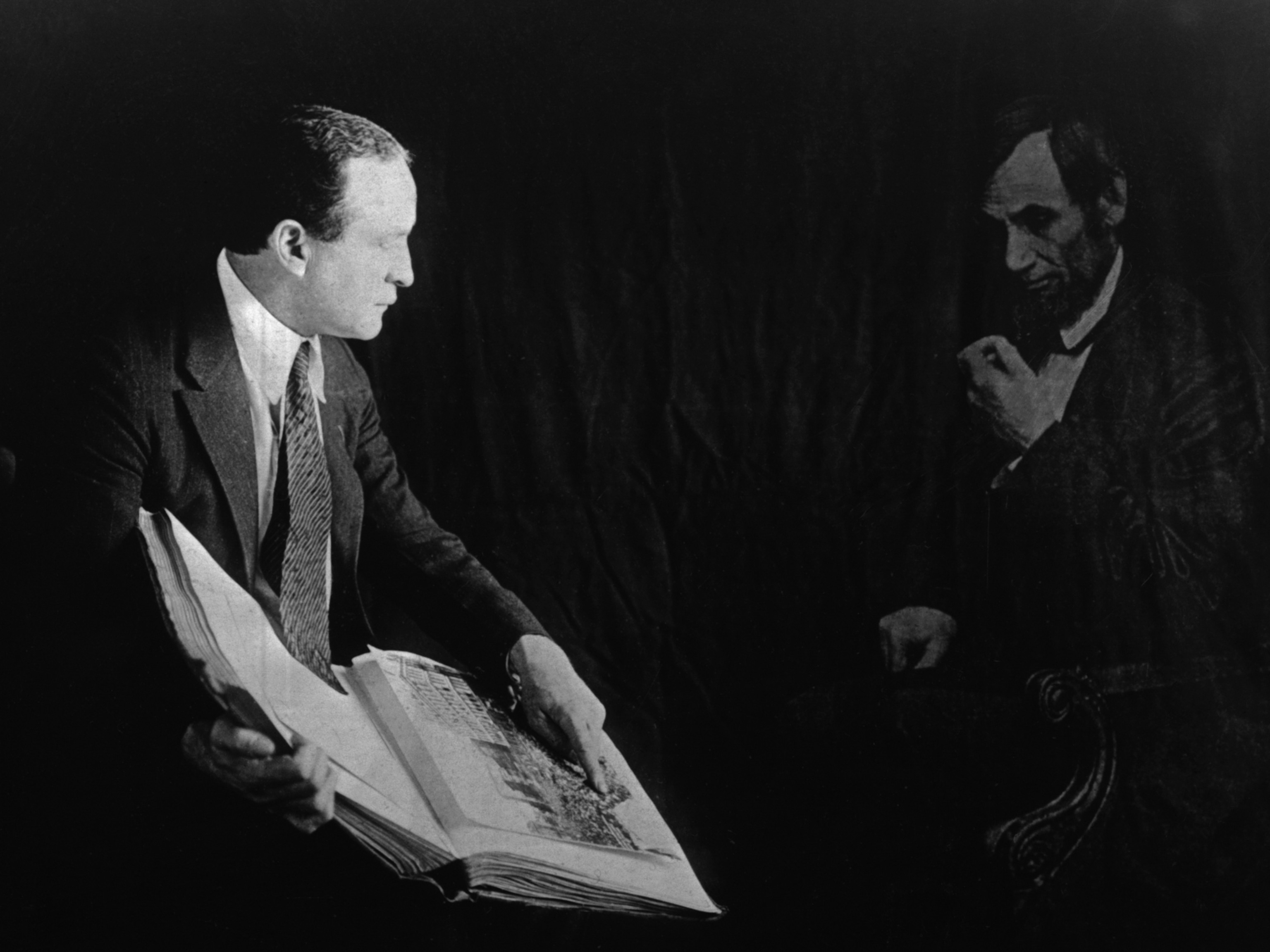

By the early 20th century, Ouija and the public had a total love affair. Spiritualism saw a massive resurgence after World War I and the devastating 1918 flu endemic. The 1920s were rife with love songs dedicated to the mystical board, and it became a beloved date game, offering a romantic way for couples to sit close to each other and pose flirty questions. Norman Rockwell, famous for his paintings of idealistic American life, even depicted a young couple on a 1920 cover of The Saturday Evening Post sitting knee to knee, with an Ouija board on their laps and fingertips touching.

A portal for demonic forces?

Over the decades, depictions of the Ouija board shifted from lighthearted and romantic to increasingly ghostly and true-crime-focused. By the late 1960s, the board’s image took a dramatic turn, influenced by events such as the Manson murders and the rise of the Church of Satan. The pivotal moment came in 1973 with the release of The Exorcist.

(The real history of exorcisms that you don't see in movies.)

The film, which was loosely based on a true story, includes a brief scene depicting a child playing alone with an Ouija board, through which she later becomes possessed. Kozik says this was the first time a film suggested that evil could come through the board in this way.

“When you see a horror movie based on a true story, that’s when you start thinking things like that could happen to you,” he says. In 1967, Ouija outsold Monopoly, the only game before or since to do so. Over two million boards were sold that year alone, setting the stage for the fear and fascination that followed The Exorcist. Subsequent horror films, including Witchboard, helped cement many infamous talking board myths that are still prevalent today.

Despite its spooky reputation, studies show that the Ouija board is simply a product of the ideomotor phenomenon—a psychological effect where people move objects unconsciously. Nonetheless, the Ouija board remains a popular activity at tween sleepovers, reflecting its ongoing appeal. Ironically, while many find it a harmless game, Kozik frequently receives boards from people who, despite understanding the science, still fear their power and wish to dispose of them.