The world’s loneliest volcano may hold something truly rare. We went to find it.

A team of scientists and explorers journeyed to an icy island volcano in the South Atlantic to search for a lake of fire. What could go wrong?

On an ice-crusted ridge 3,000 feet above the angry swell of the South Atlantic, Emma Nicholson takes a deep breath behind her respirator, checks her climbing harness, and steps inside the gaping mouth of an active volcano.

It’s a little after 4 p.m. on the wind-whipped summit rim of Mount Michael, which looms over Saunders Island. Located in the uninhabited South Sandwich archipelago, the island is one of the most isolated places a person can travel to on Earth—roughly 500 miles from the closest permanent station on South Georgia and more than a thousand miles from the nearest shipping traffic. In fact, the closest people to Emma and her expedition mates are the seven astronauts and cosmonauts aboard the International Space Station, which passes roughly 250 miles above them every 90 minutes.

But after years of planning and enduring a tortuous 1,400-mile voyage through turbulent, iceberg-infested seas, the 33-year-old volcanologist is on the verge of becoming the first scientist to lead an exploration inside Mount Michael’s crater, where she hopes to collect new clues about poorly understood processes at work deep within our planet’s plumbing.

But Mount Michael isn’t a volcano that easily gives up its secrets.

At first glance the inner part of the rim seems harmless, giving way to a gentle snow slope, no steeper than an intermediate-level ski run. Emma and her research partner, João Lages, cautiously descend on a climbing rope—their only connection to the outside world—but both understand that somewhere below, this seemingly benign terrain might end in an unstable ice cliff overhanging the inner rim of the volcano.

As they inch their way down, conditions improve: The wind subsides, and patches of blue sky appear overhead. Beyond her face shield, Emma can see a circle of near-vertical walls of ash-covered rock and ice.

Carrying a computer and a heat-sensing camera, João and Emma descend deeper into the mountain. Below them, the gentle ski slope abruptly drops off into a dim void and an unknown distance to the crater’s bottom. As she looks around, slightly wide-eyed, Emma understands she’s standing inside the rim of Earth’s chimney—a place that bears the scars of one of nature’s greatest displays of power.

For a volcanologist, it’s the quintessential career moment, being the first to peer down an obscure portal into the planet’s interior. Only one thing eludes her, the thing that brought her to this godforsaken place: Where is the lava lake?

A reassuring tug pulls against her harness. The rope, Emma knows, is connected to a most trustworthy anchor on the summit: mountain guide Carla Pérez. Over the past weeks, Emma and Carla have become close friends as they shared a cramped ship’s cabin and a quaking tent through howling gales. Without a line of sight to Emma, Carla knows that an overhanging ice cliff might be lurking somewhere in front of her friend—it could give way without warning, sweeping her down the throat of the volcano. The tug is a little reminder to Emma not to forget herself and go a step too far.

On February 2, 1775, a weary Captain James Cook stood at the aft rail of his ship, the Resolution, and stared out at a bleak, snowbound island. The mariner had been at sea on his second voyage of discovery for two and a half years, and the foreboding geography matched his mood. “The most horrible coast in the world,” Cook declared of the archipelago he’d named the South Sandwich Islands after one of his supporters, the Earl of Sandwich. These islands, he wrote, were “doomed by nature … never once to receive the warmth of the sun’s rays.”

It would be decades before scientists understood that one of them, Saunders, possessed its own source of heat. And even then, no one was much interested in visiting the icy, windswept island in the middle of nowhere.

Out of about 1,350 potentially active volcanoes in the world, only eight had been confirmed to recently host persistent lava lakes.

“The South Sandwich Islands—they’re tough to get to, tough to get ashore on, tough to work in, so you have to have a pretty good reason to go there,” says John Smellie, a geology professor at the University of Leicester. And yet, the islands, which are formed by the movement of the South American tectonic plate beneath the South Sandwich plate, are one of the world’s simplest tectonic settings to study volcanology.

“It’s effectively a crust factory,” Smellie told me when I reached him by phone at his office in England. “You can examine what happens to magmas from inception to being brought to the surface … because the variables are so few there.”

I contacted Smellie because he’s one of the few people known to have visited Saunders Island. During an expedition in 1997, he was taking samples on its north end when he noticed that the plume from Mount Michael was unusually dense. “It was huffing and puffing, and those were characteristics that surprised me,” Smellie recalled.

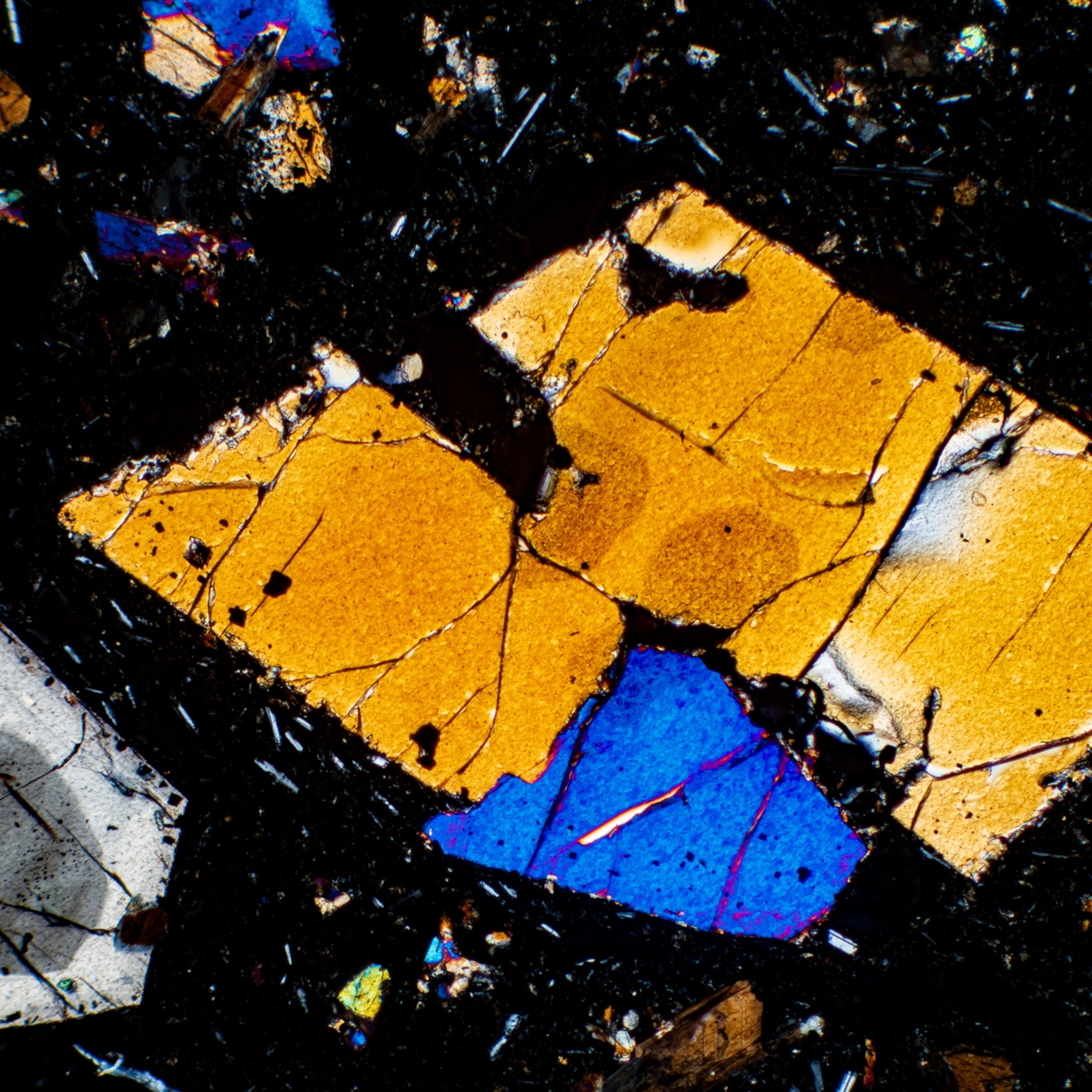

The behavior reminded him of Mount Erebus, an Antarctic volcano with a permanent lava lake. Smellie asked a friend at the British Antarctic Survey if satellite imagery could identify any thermal anomalies around Mount Michael. Using a satellite-based radiometer, they worked to identify a heat signature that corresponded to Mount Michael’s summit crater. They posited that, with temperatures averaging around 570°F, it was a lava lake: one of volcanology’s rarest phenomena.

Although there are about 1,350 potentially active volcanoes in the world, only eight had been confirmed to recently host persistent lava lakes—perpetual cauldrons of molten rock. Typically, after an eruption, lava exposed to the atmosphere will cool into a solid plug of rock, trapping the heat and gases within (and potentially priming the volcano for another explosion). But in open-vent volcanoes, the plumbing that connects the surface to the magma chamber deep below remains open. For a lava lake to form, the pressure must be great enough to push lava all the way to the surface—like the water pressure in a fountain. But for the lava lake to remain, the pressure has to continue, and the ratio between heat coming up from within the magma column and the rate of cooling must be perfectly balanced, to keep the lava in its molten state.

“Temperamental” is a good word, Smellie says, to describe the pressure levels that pump lava into Mount Michael’s crater. “It comes and it goes, possibly for months at a time, but then our research shows it persists for months at a time.”

Because open-vent systems provide opportunities for scientists to sample and analyze both gas and lava, they are considered a critical laboratory for better understanding volcanic behavior and helping predict and mitigate volcanic risk.

But Smellie was more interested in studying the rocks surrounding the volcano and never seriously considered climbing Mount Michael. “Lava lakes aren’t my science,” he says. “Knowing Sod’s Law, I’d likely pick a time when it had receded and wasn’t visible.”

In 2019, another team of volcanologists using higher-resolution satellite data updated the findings of Smellie’s team and calculated a more than 107,000-square-foot-wide anomaly on the crater’s surface. Like Smellie, they assessed it to be a lava lake, slightly smaller than one and a half professional soccer fields.

That study also caught the eye of a newly tenured volcanology professor at University College London named Emma Nicholson. As precise as the satellite imagery was, she knew the only way to confirm Mount Michael held a lava lake—and for that matter to study it—would be to climb to the rim and collect samples inside its crater.

The fact that it had been two decades since the last field geologist had worked on Saunders Island appealed to the determined volcanologist.

“When I was young, I would always be getting lost, wandering off, trying to explore,” Emma says. Her parents, both avid hikers, or “hillwalkers” as the British say, encouraged their daughter’s adventuring. One outing during a family vacation to the United States when she was six years old would have an outsize influence on her life: a ramble to view Mount St. Helens.

“All the trees were still blown down in one direction,” Emma recalls. “Ash was everywhere, even more than 10 years after the eruption. I remember wanting to understand what forces could’ve created that landscape.”

In 2020, Emma joined an expedition aboard an aluminum-hulled sloop for a survey of the South Sandwich Islands. After anchoring off Saunders Island, Emma, research partner Kieran Wood, and several other scientists attempted the first ascent of Mount Michael, only to turn around in deteriorating conditions. “Within minutes we went from almost clear blue skies to driving snow, blizzard conditions,” Emma says. “It would have been completely reckless to continue.”

Even still, the decision to turn back was gut-wrenching, and I could hear it in her voice when she said she left Mount Michael with “unfinished business.”

Last November, I joined Emma, a National Geographic Explorer, in the Falkland Islands for a return trip to Saunders. She’d assembled an expedition to complete the first ascent of Mount Michael, as well as the first on-the-ground study of its crater. The Australis, a steel-hulled motor sailer, was waiting at the dock in Port Stanley. Her captain, Ben Wallis, a lanky 43-year-old Australian with salt-and-pepper hair, greeted me in a pair of grease-stained coveralls.

Our expedition would’ve seemed tiny to Cook. Ben and two crew members provided the transportation. Emma, with colleagues João Lages, 30, a geochemist and volcanologist, and Kieran Wood, 37, an aerospace engineer and drone specialist, made up the science team. Photographer Renan Ozturk, 43, led a four-person media team. Carla Pérez, 39, an Ecuadorian mountaineer and one of only a handful of women to summit Everest without supplemental oxygen, would lead the mountaineering phase of the trip.

Ben had taken the Australis to the South Sandwich Islands once before, a harrowing experience. “I don’t talk about that one, mate,” he told me. He wasn’t alone in his dread of this stretch of ocean. Our course would skirt the Drake Passage between the tip of South America and Antarctica where the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans meet and form some of the most treacherous waters on the planet. With no landmass at this latitude to impede the wind or currents, waves can grow as tall as 40 feet.

Several weeks after I first asked him, however, the soft-spoken Ben relented and told me a heart-pounding tale of surviving a windstorm at sea that pushed past 90 miles an hour on his wind-speed indicator before he stopped looking at it.

In his more than two decades of cruising small boats around the Antarctic Peninsula, Ben routinely makes four or five round-trip crossings of the Drake Passage each summer. But it had taken a few years, he admitted, before he felt ready for another voyage to the South Sandwich Islands.

“What makes the South Sandwich Islands different is they’re outside the fence,” Ben explained. In other words, they’re beyond the reach of shore-based aircraft, and few ships travel through the region. “There is nobody to come get you if you run into trouble,” he said.

Our first day at sea, the winds were light, and we comfortably lounged on deck in windbreakers. Yet each day the temperature grew a little colder, and we spent less time above deck. Below, 12 people learned the basics of surviving at sea in 75 feet of steel: how to pass each other in shoulder-width corridors, carefully timing our trips to the microwave, and always keeping a bucket close. All the while, the Australis’s diesel engine steadily drove us up and down the swells at eight or nine knots.

Our team tried different strategies for dealing with seasickness: medication, exercise, not eating, movies, alcohol. Kieran preferred to look at the horizon, gazing out from the pilothouse for hours. Carla meditated. My lower bunkmate, João, spent 23 hours a day in his berth, staring at the ceiling. Nobody seemed to get it worse than Emma, who spent her birthday, Thanksgiving, curled in a fetal position just outside the bathroom, her body racked with dry heaves throughout the night.

“You just feel completely wretched, a shell of a human,” Emma says. “It just comes in waves. And there’s nowhere on the boat you can go.”

On the fifth day at sea we spotted South Georgia island, formerly a thriving whaling hub. In 1916, a desperate Ernest Shackleton arrived here in a tiny boat, having sailed 800 nautical miles from Elephant Island, where he’d left the rest of his marooned crew to seek rescue.

But South Georgia is only two-thirds of the way to Saunders Island. After a brief stop at the port of Grytviken, where we checked in with British authorities who manage South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands as a marine sanctuary, we left the protective shelter of South Georgia’s coast and steamed farther into the South Atlantic. Icebergs began to appear out of a hazy horizon. With the benefits of radar and a steel hull, we zigzagged between a patchwork of these enormous gleaming hazards until, finally, on the afternoon of our eighth day at sea, Saunders Island appeared abruptly out of the fog.

A minuscule five-mile-wide crescent poking out of the South Atlantic Ocean, the island offers no safe anchorages. Our best bet was Cordelia Bay, which afforded minimal protection from the wind and swell but was also guarded by shoals labeled on the nautical charts as “foul” and “unsurveyed.” As we turned toward land, the clouds that had enveloped the island dissipated, and we got our first view of Mount Michael: a low, squat, and almost perfectly symmetrical profile of a mountain—perhaps not overwhelming in grandeur but still formidable.

Ben edged the Australis under cliffs towering over the north end of the beach and dropped anchor. Suddenly there was little time to spare. A ton of equipment that had been securely stored in the forecastle was pulled out into cramped cabins as we readied to ferry it by dinghy to the beach the next morning. Time was short because Ben estimated we could stay 16 days at most before weather would force us to leave.

During the repacking, photographer Ryan Valasek let out an unexpected cry from the bridge: “Will you have a look at that!”

Everyone dropped what they were doing and climbed to the pilothouse. A shimmering, saucer-shaped cloud appeared in the night sky above Mount Michael. At first, my eyes registered deep reds and violet against the starry black night. It resembled the last light from the sun, already faded over the horizon—only the sun had set two hours ago. I slowly realized the light was coming from inside the volcano. As we stared, the color palette seemed to gently shift, the brick red becoming scarlet then orange, the deep violet softening to purple.

Standing outside in the biting night air, her hands clutching the ship’s rail, Emma shivered from both the cold and the excitement. The incandescent display we were witnessing, projected onto the underside of a cloud, was the first real sign of what she’d journeyed halfway around the world looking for: lava.

In the morning we woke early and dressed for cold-water conditions in dry suits, with layers of fleece beneath. Although the sea was calm enough that we could hop out of the Australis’s 14-foot inflatable dinghy onto the shore without difficulty, the surf was still powerful enough to nearly swamp the boat by the time we’d finished unpacking each load. It made me wonder how we’d handle such an operation in bad conditions.

The pungency of marine life greeted us on shore—part dead fish, part bird poop, part rotting seaweed. Mammoth elephant seals and smaller Weddell seals lay close to the waterline, while flocks of chinstrap penguins, gentoo penguins, and giant petrels occupied the stark brown and gray hills between the sea and the snow-covered flanks of the mountain. A cacophony of squawking rose and fell but never went silent.

To avoid any turf wars with wildlife, we chose a spot for our base camp on a shallow snowfield a half mile from the beach.

That evening the team was settling in for a dinner of tortilla-wrapped cheese dogs when Saunders Island threw its first curve. On the outskirts of camp, João and Emma were testing the acidity of the snow, which we planned to melt for drinking water. The results left Emma speechless. The island’s water supply—at least in the immediate surroundings of our camp—was undrinkable.

When Carla Pérez was growing up in a small hill town about a 30-minute drive from Quito, she dreamed of climbing the huge, snow-clad mountains of the Cordillera Occidental towering above her backyard. Her father took her climbing among small volcanoes in the region, but when she was older, he decided she needed to learn proper outdoor skills. He took her to a local mountaineering club, only to be told the club was for boys. They found another group, and soon Carla was not only climbing big volcanoes but also dreaming of one day becoming a volcanologist.

By her early 20s, Carla had earned a master’s degree in earth sciences, specializing in geochemistry, but her dream of becoming a scientist morphed into something else: She became a professional mountaineer, leading foreign climbers up Ecuador’s peaks and pursuing her own alpine goals around the world. In 2019, she became the first woman to summit both Everest and K2 in the same year.

“I realized what I love is to be in the volcanoes, outside taking samples,” Carla says. “With Emma, I feel like we have parallel lives, like mirrors.”

As Carla and Emma lay in their tent our first night on Saunders Island, Emma’s mind raced. The lack of potable water would force the end of the expedition if another water source couldn’t be found. But tainted snow was also part of the reason she’d come back to Saunders Island.

Roughly a tenth of the world’s population lives within 60 miles of a volcano, and those communities face a range of potential hazards stemming from volcanic activity. As threatening as eruptions but far less studied are the long-term effects from drinking water and breathing air contaminated by open-vent volcanoes, which often expel a brew of gases. Water vapor, carbon dioxide, and sulfur dioxide typically make up more than 90 percent of a volcano’s plume. But when lava is close to the surface, it’s also known to emit fluorine, chlorine, and bromine, all highly acidic elements. Mount Michael’s pristine snow slopes provided a perfect, undisturbed catchment zone to assess such a volcano’s impact on the water table.

“You have no external sources of pollution,” Emma said, explaining that almost “any chemical you measure in the snow or the groundwater is coming from the volcano.”

A better understanding of this process could help communities near volcanoes adapt long-term solutions, including water treatment and targeted air quality warnings. But to properly study this in the few days Emma had on the island, she’d need to systematically collect samples beneath the plume all the way to the summit.

The following day, Carla organized a team to address the drinking water problem. By dinghy, the crew ferried about 130 gallons of water produced by the Australis’s desalination machine to the beach, then Carla’s team hauled it the half mile to camp. Meanwhile, Emma, Kieran, and I spent the day scouting the mountain and collecting snow samples.

That night in her tent, as the winds rattled the fabric around her, Emma carefully melted each sample of snow into water and added nitric acid to preserve its composition for study back in the lab—a delicate operation involving a highly corrosive chemical inside a billowing shelter. She likened it to “playing with a live hand grenade.”

The next day, we made our first attempt to climb Mount Michael. We were 200 feet below the summit when a high-pitched alarm pierced the roaring wind. Emma and Carla wore sensors on their packs to alert us to sulfur dioxide. We pulled on bulky respirators underneath our ski googles and continued upward.

But as we ascended, conditions deteriorated. The wind screeched louder, and thick clouds raked the mountain. Kieran tried to launch a drone with a thermal sensor, but it immediately got caught in swirling winds and was hastily retrieved. Other tech was failing too. Several cameras stopped working, and a handheld GPS unit malfunctioned.

“We need to belay,” Carla shouted to me, indicating we needed to rope up in case there were crevasses hidden under the snow. We all clipped into the rope, and I led us into the gloom.

After a hundred feet of groping through the whiteout, I thought I’d found the rim of the crater—but in 60-mile-an-hour winds and thick fog, it was impossible to see past my hand. The rest of the group joined me. From her pack, Emma removed a briefcase-size instrument with several short pieces of flexible hose attached to it: a sensor that would record all the plume’s major gases. Kieran continued upward to recon.

Ten minutes after he disappeared into the cloud, he returned, grinning. “It’s much nicer up there. I think I found the summit.”

Soon we were all embracing on the highest point of the mountain. There was blue sky above, but thick clouds filled Mount Michael’s crater, like a witch’s cauldron. The idea of exploring inside the crater in these conditions—or waiting for the weather to break—struck us all as absurd.

We’d accomplished the first ascent, but we still had no idea what was inside.

The next day, we piled into one tent to look at the forecast and discuss options. Ben, radioing from the Australis, told us a low-pressure system arriving in a few days would create “unsafe sea conditions”—the first time we’d heard him use that phrase. We’d hoped to stay a few more days, but it was time to leave Saunders Island.

Yet Emma was adamant about returning to the summit. Between equipment failures and the extreme conditions, she and Kieran had only been able to capture a small amount of data.

“We still hadn’t really solved this mystery of whether Mount Michael hosted a lava lake at its summit,” Emma says. Furthermore, she hadn’t collected enough ice and gas samples to study the volcano’s influence on water.

A sliver of hope remained: A lull in the winds was forecast before the next low-pressure system swept in. We decided to divide the team: Kieran and I would pack up camp while Carla led Emma, Renan, and João back to the summit. If everything went right, they’d descend from the summit to the beach, where the dinghy would ferry us back to the safety of the Australis.

Carla’s tug on the rope reached Emma as she stood straining for an unobstructed view of Mount Michael’s crater floor, hoping to see a telltale bright orange patch far below. As desperate as she was to confirm the presence of the lava lake, there was other important science to attend to, notably the gas samples. The team had stationed the sampling device within the thickest part of the plume to record the highest concentrations of gases, which would provide a gold mine of data.

With the beach deep in shadows, we realized we’d have to swim off the island. I’d joked about this, but no one was laughing now.

A team of João’s colleagues at the University of Palermo had developed the sensor for a moment just like this, and as João was setting up the device on the rim, the usually mild-mannered researcher spontaneously let out an earsplitting scream: part ecstatic release, part battle charge.

While the scientists worked, Renan decided to risk flying the drone one last time, despite the unpredictable winds. As he fought to maneuver the tiny aircraft, the crater’s blackened bottom came into view on the flight controller’s video screen. The wind calmed, and suddenly there it was: the world’s ninth active lava lake. The glowing oval looked more like a pond, but Emma could finally breathe a sigh of relief. “It was unmistakably lava close to the surface,” she says, “feeding the gas plume that we were measuring.”

Meanwhile, far below, a gray sheen had covered the sea. Chunks of pack ice sucked north from Antarctica had enveloped Cordelia Bay. Some were the size of small boulders, others as big as refrigerators. “It’s all rather suboptimal,” Dave Roberts, Ben’s first mate, said over the radio.

It was too dangerous to land the dinghy on the beach, so Kieran and I, wearing the bulky dry suits, hauled our gear through the hammering surf to Ben and Dave in the dinghy anchored just offshore. For hours they shuttled loads to the Australis. Finally Emma, Carla, Renan, and João joined us on the beach with the news of the lava lake, but there was no time to celebrate.

An hour before sunset, with the beach deep in shadows, we realized we’d have to swim our way off the island. Earlier in the trip I’d joked about this possibility—but nobody was laughing now.

One by one, team members stepped over ice chunks and approached head-high surf, trying to time their swims to the dinghy between wave sets. When the last three of us remained on the beach, it was pitch-black. A pinprick of light bounced in the inky void—Ben and Dave in the dinghy, idling just beyond the breakers. They were less than a hundred feet away, but in the dark, with the waves and the minefield of ice chunks, the distance felt like a mile.

“We’re ready for you,” I heard Ben’s voice crackle over the radio. I zipped the radio inside my dry suit, then locked arms with João and cinematographer Matt Irving, and we started forward.

After a few steps, a powerful wave bowled us over. I tasted salt water and felt its sting in my nose. I popped to the surface as the swell carried me into the next wave and ducked my head, hoping I wasn’t about to get smacked by an ice chunk. My face tingled with cold. When I opened my eyes, I could see Mount Michael outlined against the night sky, but now its eerie glow was absent.

Awkwardly I dog-paddled toward the pinprick of light. The next thing I felt was Dave’s hands, the incredibly strong hands of a mariner, lifting me out of the sea and dropping me onto the floor of the pitching boat. Ben revved the engine and pointed us toward the Australis—and home.

The National Geographic Society, committed to illuminating and protecting the wonder of our world, has funded Explorer Emma Nicholson’s volcanology research since 2022.

This story appears in the November 2023 issue of National Geographic magazine.